Whilst most of Wendy’s and my time is spent considering prehistory, i.e. archaeology from before the Roman invasion, the LiDAR data is showing us monuments and sites from far more recent periods, and even earthworks created within living memory. I think it’s a really interesting question as to when “archaeology” stops and when the “modern” begins. This is a question that we have been asked by a number of people, wanting to know whether to record certain things in the LiDAR portal.

Photo © Copyright Trevor Hickman and licensed for reuse under a Creative Commons Licence.

As you can see from the example above, perhaps the nation’s youngest scheduled monument, age isn’t necessarily a primary consideration in whether a site might be considered of historic or archaeological significance. Greenham Common’s Ground Launched Cruise Missile silos were only emptied of their nuclear weapons between 1989 and 1991, just 13 years before the site was Scheduled by Historic England.

And we have plenty of other 20th Century archaeology that we certainly want to record. During the First World War a significant number of troops passed through training camps in the Chilterns, including more than 12,000 who trained at Berkhamsted over the course of the war. Fitness, discipline, marksmanship, manoeuvres, and trench-digging might have been core elements. And some of these have left their mark written into the landscape.

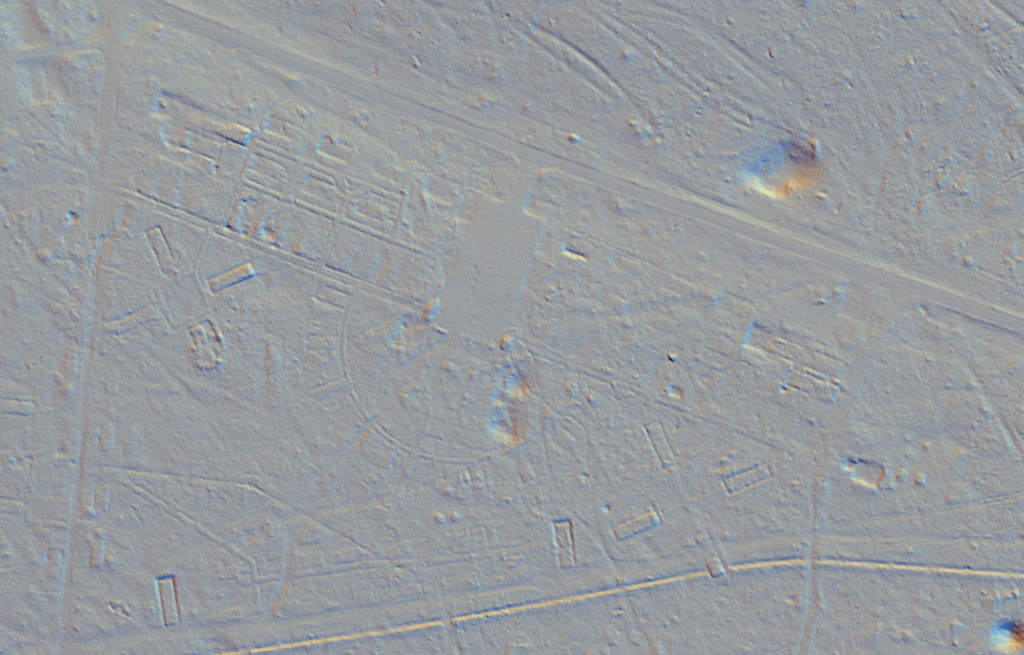

Larger and more permanent camps elsewhere in the country have left extensive remains including the imprint of building foundations: Cannock Chase in Staffordshire was home to one of the largest First World War training camps in the country, built to house around 40,000 troops during their training. These sites consisted not only of barrack buildings, but also infrastructure such as roads and drainage, and auxiliary buildings such as canteens, hospitals, theatres, post offices, and clubs. Cannock Chase has been surveyed by LiDAR, and you can view this and read more about the amazing finds discovered there on Historic England’s website:

https://historicengland.org.uk/research/current/discover-and-understand/landscapes/cannock-chase/

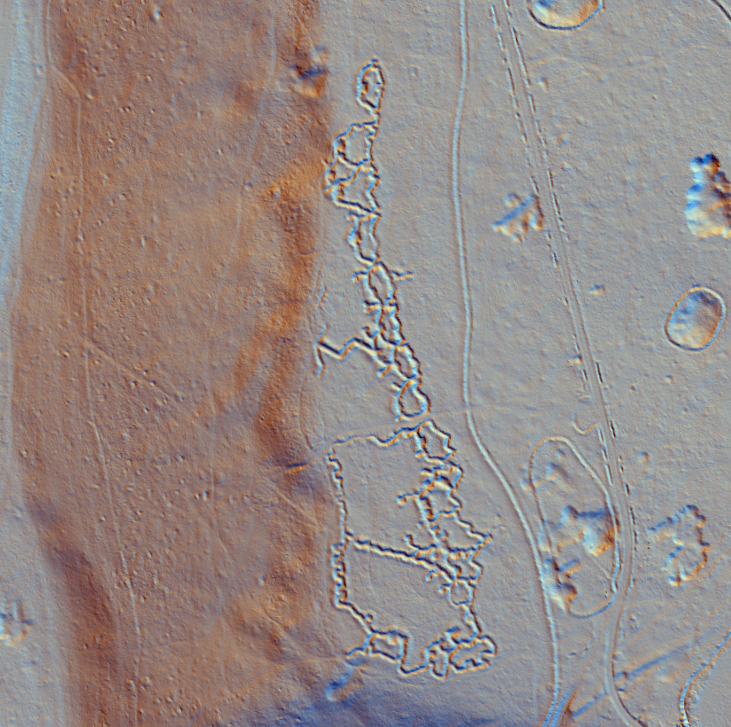

Besides structures, the construction of shooting ranges, and the digging of practice trenches will also have left their mark on the landscape, and the Chilterns LiDAR is providing an excellent means for finding and surveying these. Notable examples include training trenches on Berkhamsted Common, and others in Pullingshill Wood near Marlow. Perhaps the Chilterns provided a useful training ground for this activity, given that the geology of the British Sector of the Western Front is in many ways essentially identical to that of Chilterns.

World War II also had a similar impact on our landscape that survives in places through to today, with, for example, the ghostly traces of barracks buildings and parade grounds showing up under young woodland at Ashridge, Hertfordshire, and on Kingwood Common, Oxfordshire.

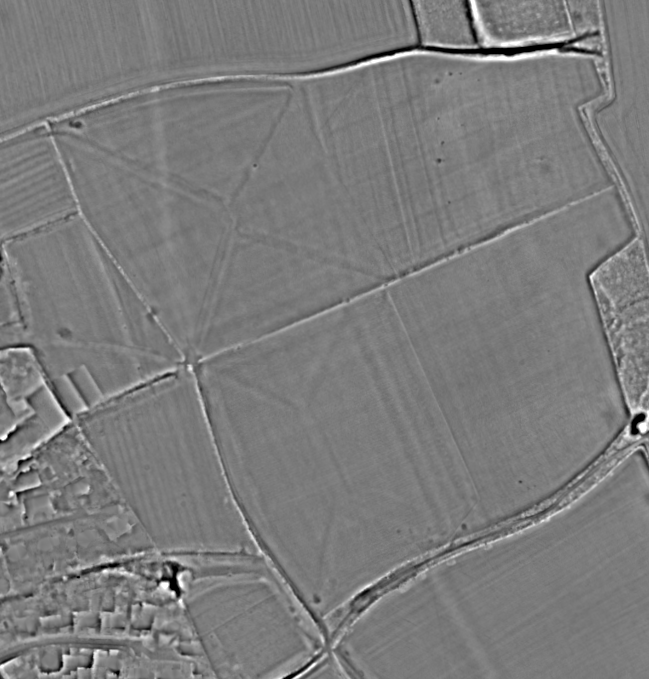

Other interesting landscape features we might want to record include the traces of a now abandoned ploughing technique: the marks left by (apparently so-called) “square ploughing” are visible in many locations in the Chiltern LiDAR: an envelope-like shape in fields, created by diagonal furrows having been left running from the corners to the centre of the land parcel.

These traces stem from the system of ploughing in a square-sided spiral running from the edge of the field in towards the centre, leaving a narrow furrow where the plough is turned at each right-angle. I have struggled to find anything written about the technique, apparently in use well into the 20th century, as evidenced by historic aerial photographs on Google Earth showing the system in action.

So how do we decide what is worth recording, and what isn’t? Rather than relying entirely on a date as a cut-off, we must consider any thing or activity that has past… things that perhaps haven’t been recorded, something that is perhaps poorly understood, or indeed things which are at risk of being destroyed or forgotten from our collective memory.

Or you could just make a mistake about the age – these remains are labelled EAW014221 ENGLAND (1948). Roman site to the north of Berkhamsted Castle, Berkhamsted, 1948 – but I’m pretty sure they are WWI trenches as that was where King George V inspected them during the war

https://britainfromabove.org.uk/en/image/EAW014221

I’ve often wondered, when you are buried, how long does it take before you become archaeology…