As you are hopefully aware, the real focus of the Beacons of the Past project is the Iron Age archaeology of the Chilterns. Whilst the LiDAR is revealing archaeology from all periods, from the Neolithic to the 20th Century, the Iron Age hillforts and their landscapes are our main concern when it comes to the project’s activities, events, and research.

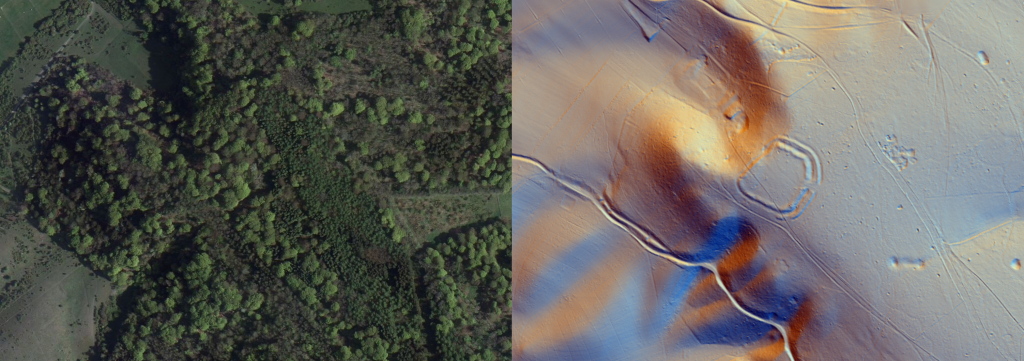

And the hillforts certainly come out beautifully in the LiDAR! I personally think they are one of the most majestic site types in LiDAR visualisations (as much as it pains me as a Romanist to say so): the sheer scale of the earthworks, if even reasonably well preserved, stand out clearly, and the generally regular shape of many of them, and relatively large area enclosed, make them dominant archaeological features in the landscape as seen through LiDAR.

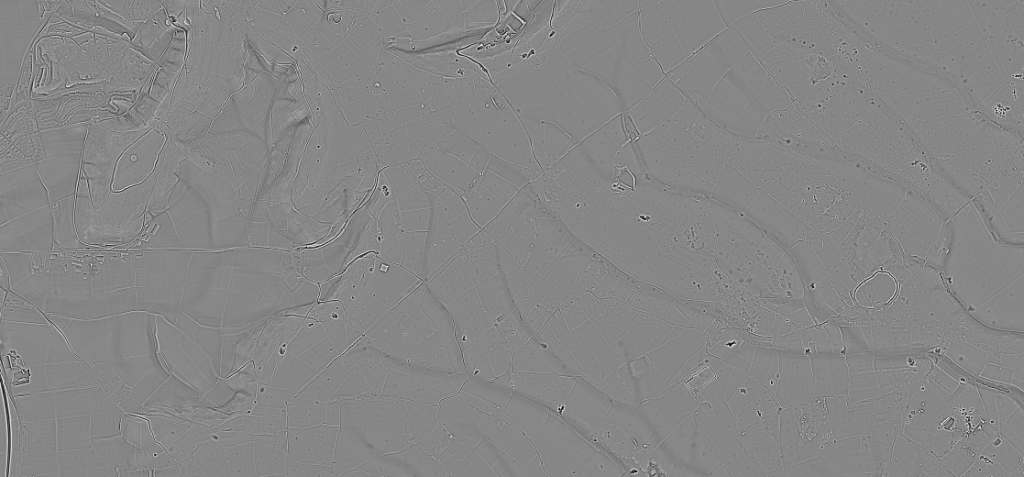

LiDAR is an excellent means by which to study hillforts. The key remains of hillforts are their earthworks, and this is what LiDAR measures. Undertaking traditional topographic survey of hillforts is arduous work, given how large they can be in length and width. Earlier in the project two teams of (admittedly student) surveyors, managed to record roughly 6 % of Cholesbury’s ramparts in a whole day of surveying. The LiDAR of course gives us wonderfully precise measurements across whole sites, permitting the creation of an accurate topographic survey with little more than the press of a button. We see the hillfort in its full plan from above or in 3 dimensions, even if some or all of it lies under tree cover.

Imagery copyright CCB.

LiDAR therefore gives us a fantastic tool for seeing the surviving structures of these sites, in their landscape setting. When you start to look at these, it becomes clear that there is great diversity in their morphology.

Some, like Whelpley Hill, Bucks., are what we would call univallate – possessing one circle of bank and ditch. Some, such as Bulstrode Camp, Bucks., we might still call univallate, but outside the ditch there is a clear second “counterscarp bank.” Others are bivallate, possessing

two banks and two ditches, either in a complete circle, or sometimes just along sections of the rampart: Pulpit Hill and Cholesbury both fall into this latter group.

The areas these sites enclose with their ramparts are also highly variable. Pulpit Hill, Bucks., is one of our smallest sites, at less than 1 ha. Bozedown Camp, above Whitchurch on Thames, Oxon., on the other hand has an enclosed area of more than 21 ha.

The shape of sites can also vary significantly. Circles and ovals might predominate, but Castle Grove Camp, Oxon. has odd straight sections of rampart meeting at angles; Boddington Camp, Bucks., has an elongated shape with a strange pointy end; and Danesfield Camp, Bucks., almost seems to be rectangular.

Additionally the landscape position of these sites is highly variable. Some are perched on hill- and ridge-tops with grand views, such as Bozedown above the Goring Gap; Pulpit, Boddington, or Ivinghoe overlooking the Vale of Aylesbury; West Wycombe Camp above the Wye Valley; or Medmenham and Danesfield overlooking the Thames. Others are in far less prominent locations: Whelpley Hill, Castle Grove Camp, Cholesbury Camp, and Wilbury Hill might all be described as sitting on plateaus rather than hilltops, offering only limited vistas of their surroundings.

With so much variation in shape, size, ramparts, and setting, we need to question whether a single term, “hillfort,” and a single interpretation of function, is suitable. Do we really believe these sites were all doing the same thing? These sites were, we think, built between c. 1100 BC and c. 300 BC… that is a long period, within which many societal and technological changes were taking place.

We believe the catch-all term “hillfort” rather conceals, and even misleads, our understanding of why these late prehistoric enclosures were built, and how they were used…. We will return soon to further dissect these intriguing monuments, to think about the many functions they may have held.